Blog

How Two Archaeologists Roleplayed Their Way to Malazan, Fantasy's Most Ambitious Series

I keep thinking about what sets the Malazan Book of the Fallen apart from everything else in fantasy.

Steven Erikson builds these absolutely massive worlds. Gods, ascendants, mortals, warrens, the whole thing. There are so many characters it's hard to keep track of and the power levels are all over the place. You've got your regular soldiers and then you've got beings that can reshape reality. The scope is almost overwhelming.

But here's what gets me. The most powerful moments in the entire series, the ones that absolutely break your heart, are when all of that massive complexity, all of that world-shaking power, comes down to rest on the shoulders of a single character.

Other authors can't pull this off the way Erikson does. He creates these situations where one person has to carry the weight of everything. Not just their squad, not just their city, but what feels like the whole damn world. And then you watch them try to bear it. That weight is bone-crushing, soul-destroying, and yet they carry it anyway.

The moments that define Malazan for me are when that character makes the choice to sacrifice themselves. Not because they're a hero or because they want glory, but because someone has to and they're the one standing there. The nobility of it, the sheer valiance of bearing that impossible weight... those moments are what makes this series unforgettable.

That's the magic of Malazan. Erikson knows how to make you feel the full weight of the world through one person's choice.

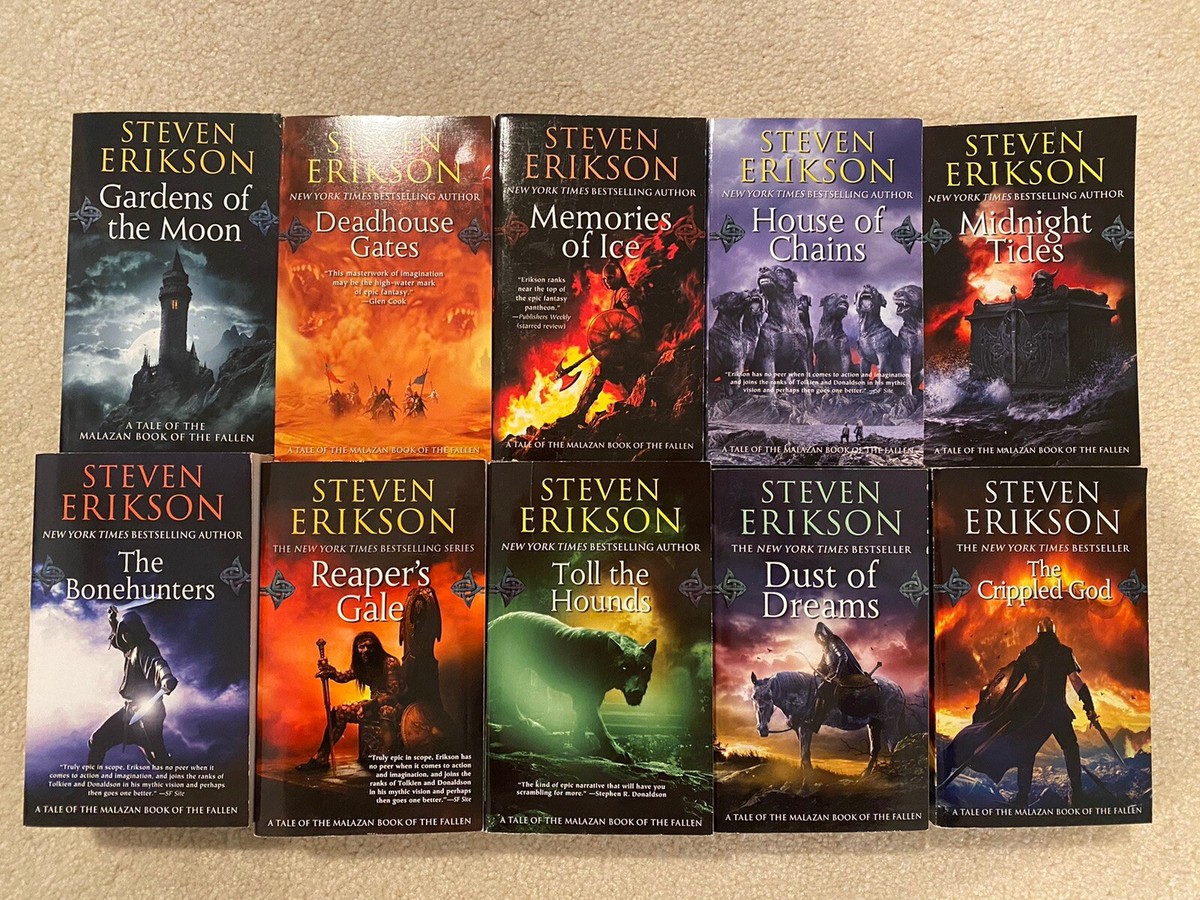

And I'm not alone in this. The Malazan Book of the Fallen has sold over 3.5 million copies since Gardens of the Moon was first published in 1999. The series holds a 4.29 rating on Goodreads with nearly 600,000 ratings. Esslemont's companion novels have sold over a million copies on their own. The series has a devoted following that treats it like a rite of passage. You don't just read Malazan. You survive it.

How Steven Erikson and Ian Esslemont Built Malazan Through Roleplaying

Here's the part most people don't know: the Malazan world wasn't written. It was played.

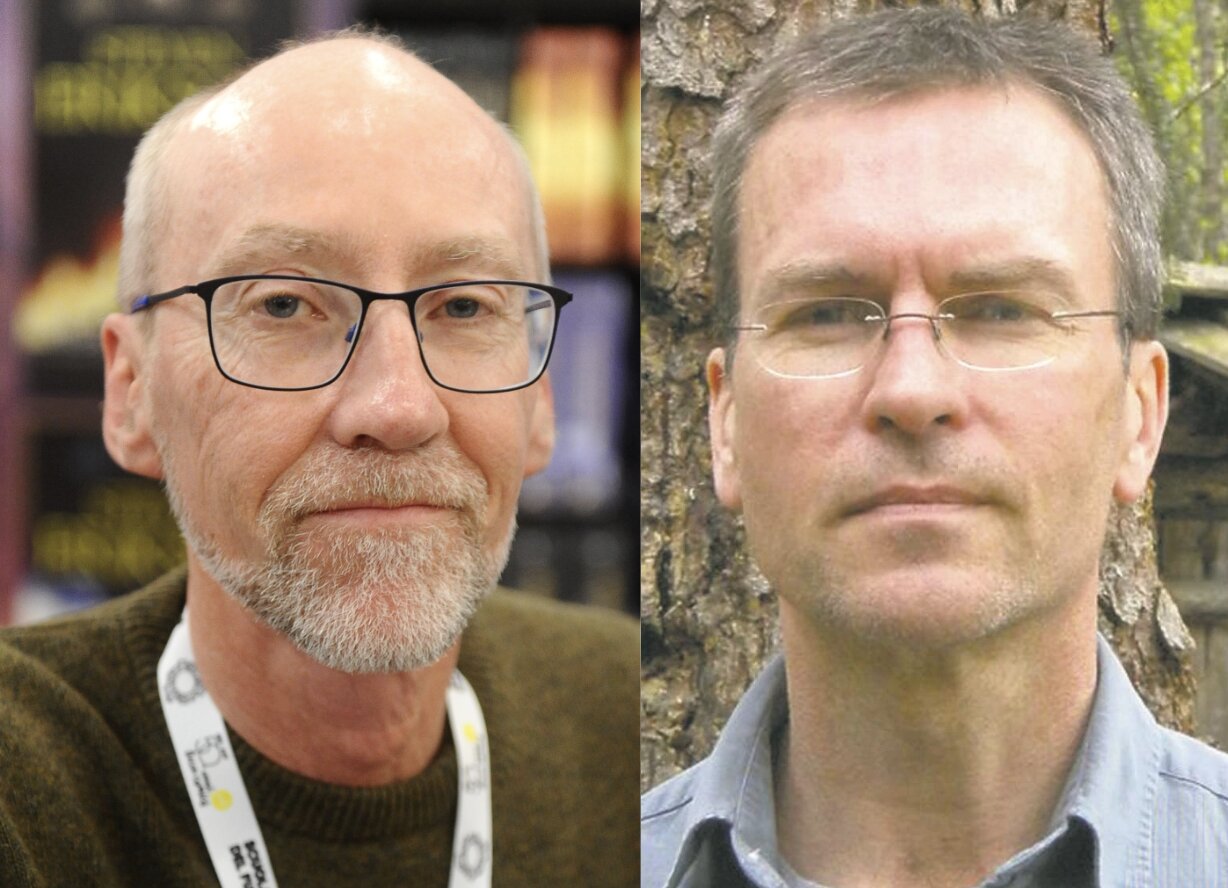

Steven Erikson and Ian Cameron Esslemont met at the University of Victoria in the 1980s. They were flatmates studying archaeology and anthropology, and they started running roleplaying games together. In 1982, they created the Malazan world as a backdrop for their campaigns.

They started with Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, but found it "too mechanical and on occasion nonsensical." So they switched to GURPS (Generic Universal Roleplaying System), which gave them the flexibility they needed. By 1986, the world had become massive, approaching the scope we know from the novels.

Their process was simple: they took turns being the game master. Erikson would run campaigns with Esslemont playing characters like Kellanved, with Dancer as an NPC. Then they'd switch. Erikson's first three characters in games run by Esslemont were Anomander Rake, Caladan Brood, and the Queen of Dreams.

Think about that. The entire rise of the Malazan Empire, all those legendary characters, the whole backstory... it was played out in one-on-one roleplaying sessions between two friends.

They had game sessions that lasted three hours where nothing happened except conversations between characters. They were building relationships, testing motivations, letting personalities emerge naturally through play. The characters developed depth because Erikson and Esslemont actually inhabited them, spoke as them, made decisions as them.

Erikson explained why they switched to GURPS: the system let them create multi-class characters that were more complex, less bound by traditional fantasy archetypes. They wanted to avoid "walking, talking cliches." Their archaeological and anthropological training influenced how they built the world. Erikson described their process: "For me and Cam, we approached world-building from geology upward. From that we slapped on layers of geography, history, anthropology and archaeology, biology and so on."

This wasn't just worldbuilding. It was world-living.

From Game to Novel

Eventually they tried to turn their world into a screenplay called Gardens of the Moon. When that didn't find a producer, Erikson wrote it as a novel in 1991-1992. It wasn't published until 1999.

That delay is important. By the time Gardens of the Moon hit shelves, Erikson and Esslemont had been living in that world for nearly two decades. The characters weren't fresh creations. They were old friends.

That's why Gardens of the Moon drops you into the middle of things with seasoned veterans. There's no farmboy discovering his destiny. The world doesn't explain itself because it doesn't need to. It's already been lived in.

And that depth you feel when reading Malazan? That sense that every character has a history that extends beyond the page? That's real. They do have that history. It was played out, session by session, decision by decision, over years of collaborative storytelling.

How to Worldbuild Like Erikson and Esslemont

Most writers worldbuild in isolation. They create wikis, write timelines, draw maps. That stuff matters. But there's something fundamentally different about inhabiting your world through play.

When you roleplay in your own world, you stop being the architect and become a resident. You discover things about your characters that you couldn't have planned. You find out how they talk when they're scared, what they value when forced to choose, how they react when everything goes wrong.

Erikson and Esslemont didn't just design the Malazan world. They lived in it. And that shows in every page.

This is why so many fantasy authors struggle with character consistency or world depth. They're building from the outside looking in. But when you inhabit your world through roleplay, whether it's tabletop RPGs like GURPS or modern AI-assisted tools, you experience it from the inside out.

This is where things get interesting for writers today.

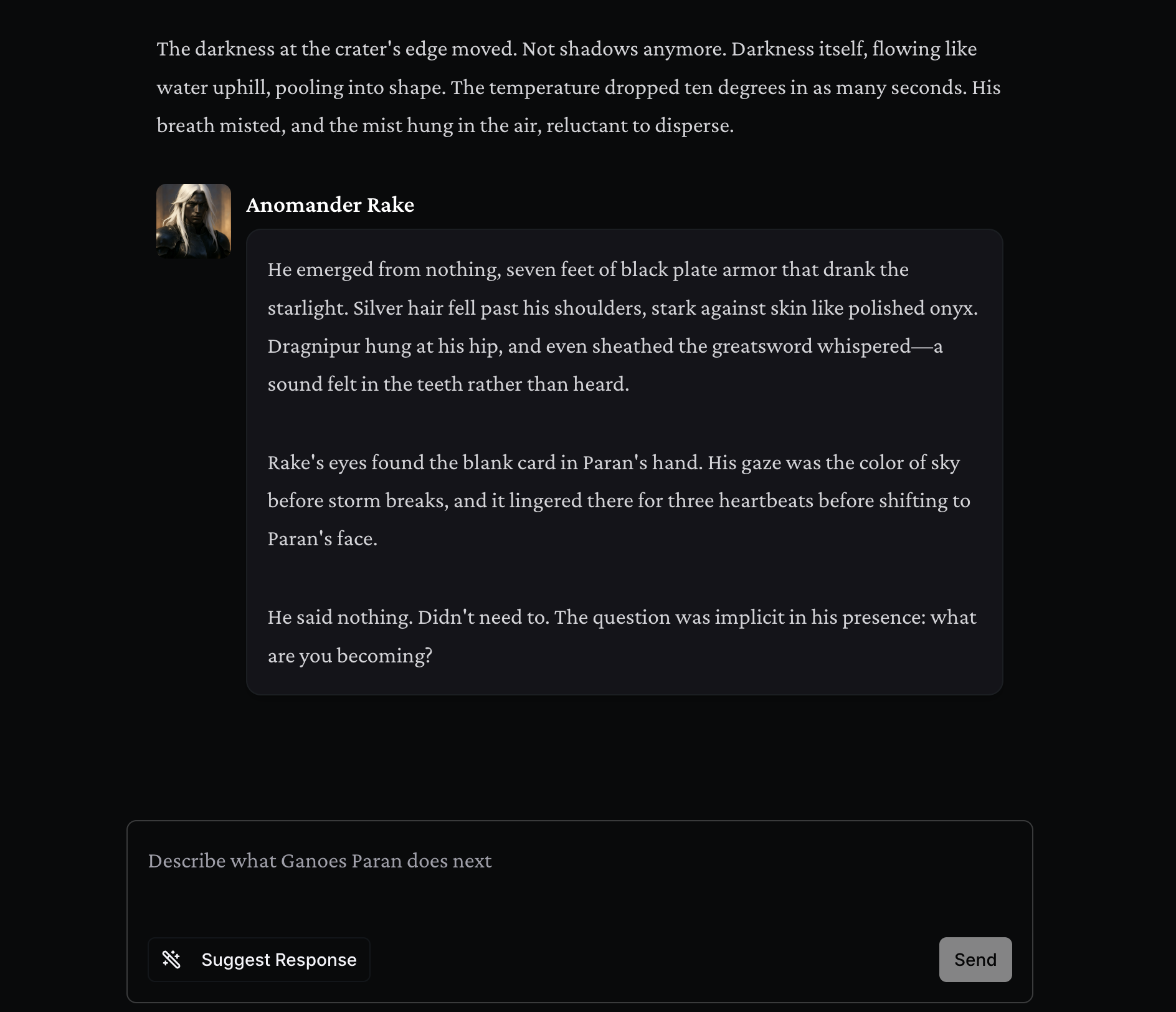

What Erikson and Esslemont did with GURPS in the 80s, taking turns as GM and player, playing out conversations and building character depth through roleplay... you can do that now. But instead of needing a friend with three hours to spare, you can use AI that understands your world, remembers every detail you've established, and helps you explore it.

That's what we built Dunia for. You create your world, define your characters, set the rules and tone. Then you can step into it. Talk to your characters. See how they respond. Watch them develop personality and voice through interaction. Test your plot points by playing through them.

The AI remembers everything. Every conversation, every detail you've established, every rule of your world. It keeps things consistent while giving you the freedom to explore. You're not fighting to make it understand your vision. You're using it to inhabit your world the way Erikson and Esslemont inhabited theirs.

And here's the other part: once you've built that world and those characters, other people can experience it too. Not just read about it, but step into it themselves. Talk to your characters. Make choices. Shape their own stories within the world you created.

Your readers aren't just consuming your story anymore. They're living in your world.

Worldbuilding Through Roleplaying: The Author's Superpower

Think about what Erikson and Esslemont gained from their GURPS worldbuilding process:

Character voice: By playing characters for years, they developed distinct voices that stayed consistent across thousands of pages and multiple books.

Relationship depth: The complementary character pairings in Malazan (Kellanved and Dancer, Anomander Rake and Caladan Brood) echo the longstanding friendship between Erikson and Esslemont. They knew how these relationships worked because they'd lived them.

World consistency: When you've spent two decades playing in a world, you know how it works. You know what fits and what doesn't. That's why Malazan feels so lived-in.

Plot testing: By playing through scenarios, they could test what actually worked. Not what sounded good on paper, but what held up when characters with real motivations had to navigate it.

This is the superpower Dunia gives you. Build your world. Play in it. Test it. Refine it. Let your characters develop voice and personality through conversation. See what works and what doesn't before you commit it to the page.

You're in control. The AI doesn't write your story. It helps you explore it. Every suggestion, every response from your characters... you approve what fits and reject what doesn't.

Then when you're ready, you can open your world to readers. Let them experience what you've built. Some might want to just read the stories you write. Others might want to step into the world themselves, talk to the characters you've created, make their own choices.

Both are valid. You decide how people experience your work.

How to Start Worldbuilding Through Roleplaying

If you want to explore your own worlds the way Erikson and Esslemont explored Malazan:

- Create a world. Set the tone, define the setting, establish the rules.

- Add characters with distinct personalities and motivations.

- Step into your world. Talk to your characters. See how they respond.

- Test your plot points by playing through them.

- Refine based on what you discover.

- When you're ready, decide if you want to let others experience it too.

The technology is different, but the principle is the same. The best worldbuilding happens when you stop designing from the outside and start living from the inside.

Erikson and Esslemont proved that creating interactive fiction and living in your world before writing it creates depth that can't be achieved any other way. Now you can do it too.

Whether you're a fantasy author developing your next novel or a reader who wants to experience interactive storytelling in rich, detailed worlds, the same principle applies: the best stories are lived, not just written.

See what happens when you inhabit your world instead of just building it.

- The Dunia Team

P.S. If you want to talk about worldbuilding, share what you're working on, or ask questions, join us in Discord.

Sources: